Track cycling had gained huge popularity at the end of the nineteenth century. Sprint races saw two riders in an explosive head-to-head battle, and after the finish the looser challenged the winner for another round. This format, resembling the gladiator fights of the ancient Rome, was adored by the crowd. Yet, to keep ticket sales up, the organisers were constantly on the hunt for novelties to make sure the people would keep coming back.

Another great day coming up. The most original race of the year

In this very context the omnium was born in early 1917. On May 8th, the French newspaper L’Auto announced a new concept to be introduced during a track meeting at the Parc des Princes in Paris one week later. They titled: “Another great day coming up. The most original race of the year.” The idea was to organise a multi-disciplinary race in order to crown the most complete cyclist. One sprinter, one stayer and one road cyclist would compete in a 1000m sprint, a 10km motor-paced race and a 20km tandem-paced race. After they had fought each other in the three disciplines, their results were added up and whoever ended up with the lowest score was the winner. It is hardly surprising that L’Auto had come up with these plans. It was indeed the same newspaper that, some fifteen years earlier, had invented the Tour de France, and clearly, they had a feeling for novel ideas. Furthermore, chief editor Henri Desgrange, who also happened to be the director of the velodrome, organized all the track meetings held there.

The rider chosen to represent the road cyclists in the first omnium was a Belgian: Charles Deruyter, who had won Tours-Paris (not to be confused with the famous race that runs in the other direction) one month earlier. Deruyter finished the first omnium in second place; the victory and the prize of 1200 francs was for Frenchman Georges Sérès. The day after, L’Auto headlined: “The public loves the omnium format.” Indeed, large numbers of people had attended the competition: “the organisers wanted to treat their crowd and had planned three races on the same day. They were rewarded with an almost ‘full house’.”

As the first omnium had proven a successful experiment, it remained on the calendar. The start list was soon extended from three to four riders, and the individual pursuit was added as a fourth discipline. The omnium turned out to be an event that appealed to crowd and riders alike. Even the biggest road racing stars ventured to the track every now and then to dispute some omnium races. These special events were of course heavily marketed by both organisers and press.

Desgrange, for example, wrote in L’Auto in 1923 that Henri Pélissier, by winning the Tour de France, had proven to be the best cyclist in the world. Much to the dismay of Costante Girardengo, who had been nicknamed Campionissimo, the champion of champions, for years. Robert Desmarets made proper use of this situation. Desmarets was the director of the Vél d’Hiv’, an indoor velodrome in Paris that used to host track meetings in the winter months. On top of this he was a journalist for, you guessed it, L’Auto – surely a conflict of interest by modern standards. Desmarets visited Girardengo in Brussels at the end of the year, where he was riding a madison race. They agreed that Girardengo would face Pélissier in a one-on-one omnium race on Christmas day. This way, the two champions could settle once and for all who was the greatest. Girardengo crushed Pélissier in all three disciplines. Even though the local hero had lost, the crowd was the big winner of the meeting. They had been so enthusiastic that the riders had to do a victory lap even before the race had started.

This story perfectly illustrates the status of the omnium races before World War II. On the one hand, the omnium attracted the biggest stars of the cycling world, but on the other hand it remained a discipline that was only organised ad hoc. Organisers used it as a crowd pleaser, and highly successfully so, since ticket sales were very high. Additionally, omnium still was not considered an ‘official’ track discipline: at the World Championships only sprint and motor-paced races were organised.

The omnium went through a process of professionalisation after the Second World War. The discipline was more systematically organised, and an international championship was introduced. From 1946 onward, one track meeting each winter was marked as the European Championship. This championship, however, was unofficial and ‘open’, which meant that it was not supported by an official cycling organisation and that non-Europeans were also allowed to start. The winner of the championship received a golden jersey decorated with vertical coloured stripes, representing the continents.

By then the range of disciplines organised during an omnium race had significantly grown. Besides the ‘classics’ – sprint, motor-paced races and individual pursuit – new possibilities had been added: the elimination race, the one- or two lap time trial and the points race. It was up to the race organiser to choose which disciplines he wanted to schedule. In reality however, sprint disciplines were chosen less and less, in favour of endurance disciplines. Requiring more endurance and less explosive power, this clearly favoured road cyclists, who were lured to the track by this trend. After all, they were in with a shout of victory, it was a good training during the winter months, and there was an opportunity to win some extra prize money. The organisers from their side were more than happy to welcome these star names at the start line.

Between 1946 and 1959, fourteen unofficial European Omnium Championships were held. They were dominated by Rik Van Steenbergen, who won no less than seven titles. Victory didn’t come cheap though, as he had to beat Tour de France-champions Fausto Coppi, Ferdi Kübler, Louison Bobet and Hugo Koblet. After fourteen unofficial editions, the European Championship was finally institutionalised in 1959. A brand new organisation, the Union Européenne des Vélodromes d’hiver, became the governing body behind the championship. In 1972, the Omnium Euro’s were finally integrated by the International Cycling Union (UCI).

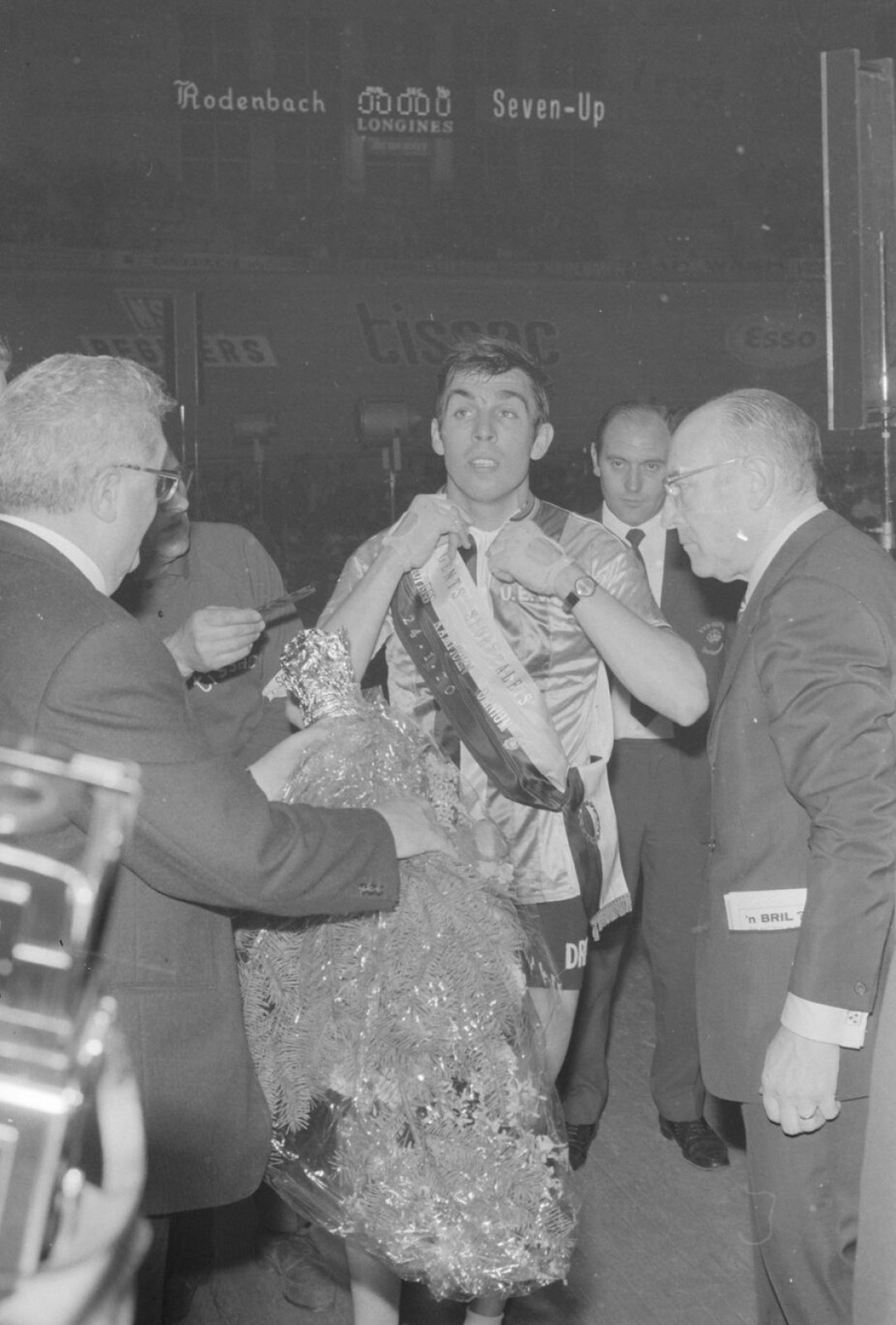

After World War II, Belgians dominated the omnium for more than thirty years. After his seven unofficial titles, Van Steenbergen was also the first winner of the ‘official’ European Championships in 1959. In 1965, young Patrick Sercu burst onto the scene. In the two subsequent decades, he would without a doubt become the greatest omnium rider ever. He took home no less than eleven European titles, and won his last medal at age 37. Eddy Merckx too figures on the palmares of the European Championships. Even though Merckx was repeatedly beaten by Sercu, who was the faster sprinter of the two, he managed to win the gold medal in 1975. In the eighties Belgian cycling, both in road and track cycling, sunk into a deep depression. The track stars were no longer Belgians, yet international riders like Urs Freuler or Danny Clark became the leading names of the velodrome. Etienne De Wilde is the only Belgian who managed to win a medal since: he became European champion in 1989.

Endurance disciplines were still favoured over sprint disciplines: points race, elimination and individual pursuit were now the cornerstones of the omnium. It led the UCI to decide that from 1995 onwards, two European Omnium Championships would be held: a sprint omnium and an endurance omnium, each consisting of four disciplines. The former was to organise the disciplines that require explosive power (keirin, elimination, one-lap time trial, sprint) and the latter the endurance disciplines (also elimination, points race, scratch and individual pursuit). With this change, the original concept of omnium was abandoned. The name ‘omnium’ no longer signified a race that sought to reward the most versatile track rider, but now just meant a multi-discipline track cycling competition.

The UCI had even further plans with the omnium. It decided in 2006 that omnium would be added to the programme of the World Championships one year later. The motive behind this change was exactly the same as that of Desgrange ninety years earlier: the UCI was looking for novelties to boost the popularity of track cycling. Alois Kankovský from the Czech Republic became the first Omnium World Champion at the Palma de Mallorca velodrome. Two years later, the International Olympic Committee also followed: the omnium would become an Olympic discipline at the 2012 Games. The Dane Lasse Norman Hansen won the first Olympic gold medal in the London Velopark. Omnium racing had finally reached the highest stage.

The story of the women’s omnium is way shorter. In 2009, they too got an Omnium World Championship. Australian Josephine Tomic became the first champion. In 2010, no less than 65 years after their male colleagues, the women’s European omnium championship was introduced. And for the women too, an Olympic title was up for grabs for the first time in 2012. In London, home favourite Laura Trott delighted the crowd by snatching the gold medal from American Sarah Hammer during the last discipline, winning by one single point.

The Belgian track women were competitive from the get-go. Race organiser Patrick Sercu decided in 2011 to add a women’s omnium to the programme of the Six Days of Ghent. In the first years the race was organised during down-time and without a star-studded field, but as the years went by the women’s omnium received a more prominent place on the schedule and the start list became more and more international. Jolien D’Hoore participated in this first edition and animated the race. Two years later she scored her first win in Ghent in convincing style, as she won all six disciplines of the omnium.

D’Hoore’s first win in Ghent proved the stepping-stone to bigger successes. During the 2016 Olympic omnium in Rio de Janeiro, she displayed impressive form and consistency, going into the final discipline second in the standings. By now it was already clear that an untouchable Laura Trott would win back-to-back titles. In a thrilling battle for the silver medal, D’Hoore was ultimately bested by Sarah Hammer, but she was over the moon with her historic bronze medal nevertheless. After all it was the first female Olympic medal in Belgian cycling history. Her medal is symbolic for other reasons still: omnium racing was only a few months away from its hundredth birthday. A century of history that started with a simple idea: to sell more tickets. And with a Belgian who participated and battled for victory. One hundred years later, the omnium had finally obtained its spot at the highest stage: the Olympics. With, again, a Belgian on the podium!

The Rio Olympics also meant the end of an endless chain of reforms by the UCI in the ten previous years. The cycling union wanted to shape the omnium into a set formula, but did not seem able to decide how many or which disciplines it wanted. What followed was a series of experiments with omnium races existing of four, five or six disciplines, with combinations of different sprint and endurance events. After Rio 2016 the omnium was fixed on four disciplines: scratch, tempo race, elimination and points race. With this change none of the ‘classic’ disciplines is still part of the omnium, and only the endurance disciplines remain. The UCI concluded that sprint disciplines, often with a standing start and some waiting time between heats, are not exciting enough for spectators. The original omnium-idea, rewarding the most versatile track rider, has therefore disappeared. What remains is a race that is, indeed, thrilling to watch, but no longer breathes history.