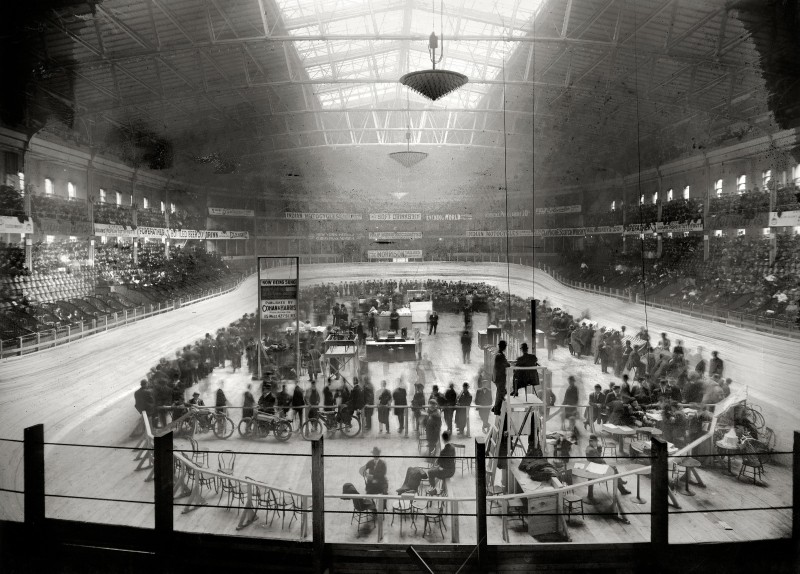

From 1900 onwards, cycling gradually became the people's bread and butter. Road races still outweigh those on the many tracks, where thousands of supporters marvel at not only six-day events, but also sprint duels and pursuits. The 'speed' factor is particularly popular. With tandems or other multi-sitters - often five men in a row - as a pacer, riders whizz over the oval at high speed. When real motorbikes appeared on the track, races with pacing - 'motor pacing' or stayer cycling - gained momentum. Spectators saw riders with a special kind of bicycle - a 'twisted' fork was supposed to provide more stability - race over the concrete track behind a heavy motorbike at ninety kilometres an hour. In order to benefit optimally from the engine's suction power, the riders race as close as possible to their pacemaker. Noise, spectacle and danger guaranteed...

It doesn't take long before stayer sports have their first fatalities on their conscience. In his own country, the Antwerp resident Charles Verbist is the most famous victim. He crashed in 1909 at the Brussels Karreveld velodrome. There are also fatalities in Germany, where the motor pacing becomes very popular very quickly. The German government intervenes and issues a ban, until it reverses its decision under massive protest. But from now on, the sport of stayer cycling is subject to a number of additional laws: riders are obliged to wear a helmet and the motorbikes are equipped with a roller, so that the riders can no longer stick too closely to the motorbike. After the First World War, a real circuit of itinerant riders and pacemakers is created, who run the show in both Europe and America. Ostend-born Charles Verkeyn is one of them.

At the outbreak of World War I, the young Charles (b. 1897) fled to France. After a short stop in Bordeaux, he moved to Paris in the course of 1915. There Verkeyn became a worker at the Renault car factory, which in this period also manufactured weapons. He sacrifices all his spare hours to cycling - the exiled citizen of Oostende dreams of a career as a cyclist. In the spring of 1916, Verkeyn receives a licence as a professional cyclist. He makes a great debut and wins Paris-Trouville in August of that year. In the winter of '16 and the spring of '17 Verkeyn builds an excellent reputation. His Parisian sponsor and bicycle manufacturer Desvages likes to show off the young Verkeyn's achievements in newspaper advertisements. When Charles is forced to start without a teammate at a meeting in the Paris Velodrome d'Hiver in April, he receives a lot of support from the track management and the public. The organisers held a collection "for the benefit of this courageous little boy", which, according to the newspaper Het Vlaamsche Nieuws, "brought in a pretty penny". In this period Verkeyn also manages to distinguish himself on various French tracks, especially in the motor-paced racing, which seems to be written out for him. In mid-July 1917 he won two of the three series in a stayer race. He beats the Belgian specialist Leo Vanderstuyft, who according to De Belgische Standaard "was not trained enough and could not possibly keep up with the fast pace, the 60 km in 45 minutes".

When the new French winter season got underway in the Paris Velodrome d'Hiver in mid-October of that year, Verkeyn was already listed as one of the favourites in the newspapers. He competes in the Poule des Nations together with renowned stayers such as Bobby Walthour, Italian Giorgio Colombatto and Frenchman Louis Darragon. He does not win, but it is significant that he is at the start of the opening meeting of the season. In April 1918 Verkeyn tasted the dangers of his sport at first hand. During the Grand Prix de l'heure the French vedette Darragon falters with his pedal during an overtaking manoeuvre. The Frenchman became unbalanced and collided with the track at a speed of around 70 km per hour. The pillion rider of Verkeyn, who was following behind, was just able to avoid Darragon, while Verkeyn first drove over Darragon's legs and then, at the bottom of the track, made a violent collision with an official. The three victims are immediately given first aid but for 35 year old Darragon all help comes too late. Verkeyn, on the other hand, suffered no permanent injuries as a result of his accident.

After the First World War, Verkeyn continued to develop his career. In the winter of 1920 he wins a prestigious race in the Paris Winter Velodrome, which immediately gives him a ticket to America, at that time the Promised Land for everyone active in the stayer sport. His first season on American soil (May-September 1921) results in a sixth place on the American stayer ranking with as highlight a victory in the prestigious Golden Wheel meeting in Boston. In 1922 he finished in seventh place, with seven victories, eight second places and fourteen third places. Before him top riders like the American George Chapman, compatriot Victor 'Sioux' Linart and the Italian Vincent Madonna finish. Madonna was a tough customer for Verkeyn during a sensational pursuit race - in this discipline too Verkeyn stood his ground - on American soil in 1923. Verkeyn draws the longest straw and manages to overtake Madonna - after 127 kilometres (!). His average speed is over 70 kilometres per hour...

In 1924 Verkeyn stranded second in the American stayer rankings. Far behind Chapman but good for 17 victories. The Flying Belgian, as Verkeyn is called in the States, runs with the top and is very popular with the American fans. In 1925 he took eleven victories. During his five-month stay on American soil that year, Verkeyn contests a total of 64 races, 21 meetings in August alone. The Austrian crashed only once when the lights suddenly failed on the velodrome in Worchester. Verkeyn returns home with - besides the many dollars - two beautiful trophies and a particularly fine gold medal, studded with diamonds. Still in 1925, according to various newspapers, Verkeyn had himself converted into an American, only to have assumed Belgian nationality again according to later reports. In any case, the comings and goings of the Amerco-Belgian were closely followed in the Parisian media - the public of the French capital had clearly not forgotten Verkeyn. Verkeyn in turn tries to cash in on this popularity. Not only by collecting nice start- and prize money in the winter velodromes (after the American season Verkeyn shifts to the Parisian and other European tracks) but also by starting his own business in the Paris region. He becomes the owner of a bicycle and motorbike shop in Meudon.

In October 1927, Verkeyn was doubled five times during a meeting in the Netherlands. "Does he feel the weight of the new world in his legs, as soon as he is back on land in Europe", a journalist of Het Rotterdams Nieuwsblad wonders. Verkeyn ends the American season that year with only 2 victories, a fraction of what he used to win, and can no longer perform consistently in Europe either. In 1928 he does not travel to America anymore and concentrates on the Belgian tracks. Verkeyn was not able to win a Belgian title in that period, Victor Linart was too strong. But in 1931 he does set a record on the Ter Rivieren cycling track in Antwerp. Verkeyn covered 100 km in just over one hour and twenty minutes... In 1932 he lost out to Emiel Thollembeek on the BK race.

A letter from the Belgian Cycling Federation (BWB) proves that Verkeyn is no longer one of the top cyclists. The BWB only wants to take Thollembeek to the World Championships in Rome in '32. Verkeyn could join, provided he paid all his own expenses... Verkeyn may have considered participating at his own expense, because on the back of the letter he noted in pencil the distance Paris-Rome (1320 kilometres) and the total weight of his luggage (200 kilos). The selection story almost has a happy ending when the BWB is allowed to send two stayers after all. Unfortunately for Verkeyn, the federation ultimately selects 43-year-old Linart, who by then has already collected four world titles and 15 Belgian titles. The Flying Belgian doesn't give up and tries to revive his career. This is evident from the correspondence kept by the family, in which Verkeyn recommends himself to various track managers at home and abroad. But a contract is no longer self-evident and hefty salaries, like in America, are no more talk of.

On 22 September 1935, Verkeyn contested a stayer race for the last time on the Ostend cycle track. After a few wanderings through Paris and Ostend, he finally settled in the Koerslaan in Bredene. There he started his own bicycle business, but above all he worked on a comeback. No longer as a rider, but as a pacer. Verkeyn is active on the Antwerp slopes and competes in 1938 in Bordeaux-Paris as a pacer on a derny - a motorbike halfway between a bicycle and a motorcycle - which was allowed in this marathon race for the first time that year. In 1939 he starts in this race as entraîneur for Marcel Kint and finishes 5th. After the Second World War, Verkeyn became a valued pacer for top cyclists such as Leon Declercq, the Breton Oscar Goethals and later also André Leliaert from Bruges, with whom he became Belgian champion in 1949.

In 1955 Charles Verkeyn starts for the last time in a stayer race. During the Belgian Championship he is called up by the Belgian Cycling Federation to replace Hendrik Van Walle's regular pacer. After that, the stayer cloth falls definitively for Verkeyn. His beloved sport is not doing very well at the moment. In the mid-fifties dernies are used for the first time during the Six Days. These motorbikes are a lot cheaper than stayer bikes but especially much easier to ride behind. Despite the lower speeds behind a derny, the invention of the Frenchman Roger Derny competes with the stayer bikes relatively quickly on the track. Also because the stayer sport has become a victim of its own success. Stayers are almost completely dependent on their pacemaker/entraîneurs for their success, which opens the door to combines. In the meantime, the number of velodromes is dropping rapidly and cycling fans are focusing on road cycling rather than the track.

In spite of everything, a few Belgians are still in the world top. Verkeyn just witnesses the world titles of Theo Verschueren in 1971 and 1972. In 1973, Charles Verkeyn dies. Nothing is left of his many dollars. To give him a decent appearance on his deathbed, he begs his family for a nice shirt; the stayer himself has nothing left. Only three trophies, a number of framed portrait photos and a stack of carefully kept paper souvenirs remain. In the meantime, the sport of stayer cycling is drifting further towards the abyss.

Stan Tourné became multiple Belgian champion, but at the end of his career he had to watch how the UCI decided in 1994 that it would no longer organise a World Championships for stayers. A number of track directors from the Netherlands and Germany and the Union Européenne de Cyclisme (UEC) offer the sport a last resort: the track directors by including a sporadic stayer meeting in their programme, the UEC by organising a European championship stayer. Verkeyn himself is forgotten, until the municipality of Bredene decides to honour its own cycling heroes in 2016. On the roundabout of the Breeweg in Bredene, a giant bicycle is placed, together with a sign commemorating three local cycling heroes: Marcel Seynaeve (stage winner in the Vuelta), Oscar Goethals and his pacer and former stayer Charles 'The Flying Belgian' Verkeyn.

Just a few seconds more and the doors of Madison Square Garden would open. The atmosphere was grim. There was pushing, kicking, hitting and...